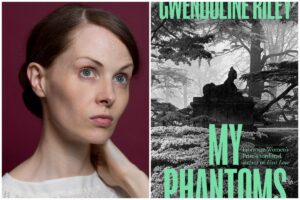

My Phantoms by Gwendoline Riley review – broken familial bonds

Between generational grinding is not really new, yet it seems like the pressure among boomers and their millennial kids is more loaded than expected. From one viewpoint, you have a partner who own their homes and can think back on existences of movement and monetary security; their youngsters, in any case, are perma-tenants squeezing out their presences in unsafe positions and fricasseeing their emotional wellness with online media. It’s fruitful ground for fiction and few have an outlined the area better than Gwendoline Riley.

My Phantoms is Riley’s seventh book in a profession that started in her mid 20s and has now extended over just about twenty years. Her books are told in the principal individual, consistently according to the viewpoint of a mysterious, somewhat removed female storyteller whose dependability is bit by bit uncovered to be suspect. Here we meet Bridget Grant, girl of guardians who isolated some time in the past yet who each keep a wild and inflexible hold over her. This is notwithstanding the way that she scarcely sees her mom, Hen, while her dad, the wildly dreadful Lee, passed on quite a while prior.

Riley’s books get under your skin. My Phantoms is disrupting for some reasons – the manner in which it picks at the scab of unlimited love, the manner in which it examines inquiries of legacy and impact. More than anything, however, it’s the way that it works on the conservative among peruser and storyteller, requesting us to look at the normal bond from compassion that springs between the narrator and her crowd.

So it is that, thinking we are perusing a novel with regards to a couple of similarly horrendous guardians, we start to scrutinize Bridget’s status. Can any anyone explain why she demands avoiding her mom, never permitting her into her home? Can any anyone explain why her own life appears to be unfilled to the point that her associations with her bloodless sweetheart, John, and her sister, Michelle, come up short on any feeling of warmth or delight? At the point when Hen has a mishap and Bridget goes to care for her, we sense the chance of a rapprochement. All things being equal, with calm fierceness, Riley diagrams the inconceivability of correspondence, the violence with which each safeguards their region. The end, when it comes, is annihilating, dreary, remarkable.