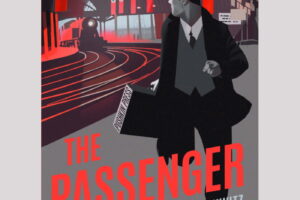

The Passenger by Ulrich Alexander Boschwitz review – on the run in Nazi Germany

There was a danger that the account of this book may overpower the story in the book – its starting point story is very something. It was written in a four-week fever following Kristallnacht, the slaughter in November 1938 that flagged the deadly idea of the Nazi aim towards Jews. The creator was a 23-year-old German Jew who had got out three years sooner, advancing toward England through Sweden, France, Luxembourg and Belgium.

His name was Ulrich Alexander Boschwitz, and however he distributed an early form of his novel in England and France, barely any saw it. When war broke out, he was considered an “foe outsider”, interned alongside a large number of other Jewish displaced people on the Isle of Man. From that point he was expelled to Australia, interned again in a jail camp in New South Wales before at last being redesignated a “agreeable outsider” and permitted to get back to England in 1942. He was on a troopship heading back when it was destroyed by a German submarine, killing him and 361 others. Over 70 years after the fact, the first German composition for The Passenger turned up in a Frankfurt document, permitting a supervisor to reexamine the novel in accordance with guidelines Boschwitz had passed on in letters to his mom. It’s the interpretation of that new text that has been affectionately distributed by Pushkin Press.

Convincing however the genuine story is, it’s outperformed by the story between the covers. The focal person is Otto Silbermann, an effective, marginally smug money manager in Berlin who tracks down his reality imploding in the hours that follow the evening of broken glass. He is Jewish, yet as of recently that had been a coincidental reality. There’s nothing apparently Jewish with regards to him, he advises us regularly; his significant other isn’t a Jew. Maybe, this is a mark the new leaders of the nation are unyieldingly forcing on him and which he can’t get away: it is the J stepped in his identification.

From the beginning, the tension on him is exceptional. It comes as brutality, as brownshirt hooligans beat on the entryway of his home driving him to escape into the evening, and in the chillier state of previous business partners who, recognizing a chance, push him to sell the structure he lives in at a knockdown cost or, in all likelihood deny him of his legitimate portion of the organization he fabricated. In this new environment, even the individuals who once affirmed companionship or unwaveringness avoid the individual set apart with the red letter J.

Silbermann turns into a man on the run, jumping on and off trains mismatching Germany. From the outset, each excursion is important for some unclear methodology for endurance – at one point he attempts to make an illicit break across the boundary into Belgium – however soon there is no genuine objective, just urgency and in the long run deterioration: he is perpetually voyaging yet going no place. There is pressure, as Silbermann tries to avoid the people who may really take a look at his papers, depending on his Aryan hopes to mix in as individual travelers welcome him with a “Heil Hitler!”, yet there is likewise the dreamlike, thickly claustrophobic environment of a genuine bad dream – a man rehashing a similar move again and again, his objective for all time far off. The outcome is a story that is part John Buchan, part Franz Kafka and entirely arresting.

It is additionally uncannily perceptive. “Maybe they’ll cautiously disrobe us first and afterward kill us, so our garments will not get wicked and our banknotes will not get harmed,” he composes. “Nowadays murder is performed financially.” That peruses like a hunch, not just of the interaction that would come almost four years after the fact, as Jews were stripped bare prior to entering the gas chambers, yet additionally of the Nazi assurance to separate every single pfennig from their casualties, in any event, pulling gold teeth from the mouths of the dead.

There is comparable premonition in Otto’s regret: “Nobody stands up to. They all recoil and say: we must choose between limited options, however in all actuality they’re glad to come in light of the fact that there’s something in it for them.” It’s as though Boschwitz predicted the complicity of the large numbers who were spectators to the evil that occurred directly before them. The author’s censure isn’t restricted to Germans or the individuals who lived under Nazi occupation, however reaches out to the free world who kept their entryways shut to Jews in human need of asylum. “Where might I go?’ he says to a lady who gullibly proposes he just leave the country. “No spot will give me access.”

Boschwitz was an adroit onlooker of his time, yet his story actually reverberates almost a century some other time when discrimination against Jews is on the ascent again and the prohibition of the individuals who are distinctive remaining parts a vindictive steady across the globe. Plus, a portion of his experiences are immortal. In a comment that will definitely ring with individuals from any minority, Otto takes note of that any blemishes he may have, any wrongdoings he may have perpetrated, are taken as proof of the apparently inborn imperfections of his gathering. “I don’t reserve the privilege to be a customary person,” he says. “More is requested of me.”

The Passenger is a holding novel that dives the peruser into the melancholy of Nazi Germany as the haziness was diving. It had the right to be understood when it was composed. It absolutely has the right to be understood at this point.