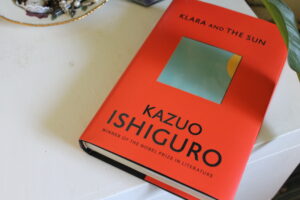

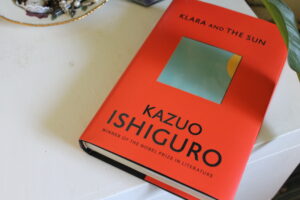

Klara and the Sun by Kazuo Ishiguro review – another masterpiece

In a 2015 meeting with the Guardian, Kazuo Ishiguro uncovered what he guaranteed was his “filthy mystery”: that his books are more similar than they may at first appear. “I will in general compose a similar book again and again,” he said. It appeared to be an especially preposterous assertion from a just followed an essayist clone sentiment (Never Let Me Go) with an Arthurian epic (The Buried Giant). With Klara and the Sun, his eighth novel, however, it seems like Ishiguro is bringing that filthy mystery somewhat more into the light. This is a book – a splendid one, incidentally – that feels a significant piece with Never Let Me Go, again investigating being not-exactly human, drawing its force from the most obscure shadows of the uncanny valley.Klara is an AF – an Artificial Friend – androids purchased by guardians to give friendship to their teen kids, who, for reasons that become more clear throughout the span of the book, are self-taught by “screen teachers” in the original’s contaminated and restless future America. Klara is picked by Josie, a delicate young lady who we before long learn has a sickness that might kill her as it killed her sister. Likewise with Never Let Me Go, one of the colossal joys of Klara and the Sun is the manner in which Ishiguro just trickle feeds to the peruser clues and ideas about the state of this advanced world, the explanations behind its peculiarity. We are left to do a large part of the envisioning ourselves, and this makes the original a satisfyingly synergistic read.

Josie and her mom take sun based fueled Klara from the retail chain where she had gone through her days being moved starting with one stand then onto the next, watching the sun on its way across the shop floor, to a house in the open country. Here we become mindful of one of the peculiarities of the book: AFs see things distinctively to people, seeing the world as a progression of squares or boxes, periodically messing up so points of view are slanted, everything given a headache ish incline. It’s only one of a progression of manners by which Ishiguro brings us into the presence of the aware non-human, one of the unpretentious contacts that clue towards the more profound subjects that are being investigated.

We become familiar with somewhat more with regards to the horrible scientism of this world when we meet Rick, Josie’s neighbor, who lives with his mom in the solitary house for a significant distance around. Rick is respectable, committed to Josie, a beginner creator of robots. He is, however, not one of the “lifted” – the hereditarily improved “high-rank” class – and hence prevented admittance to the life from getting training and progression that, should she endure, lies ahead for Josie. It’s just towards the finish of the original that we comprehend the horrible lottery that guardians in this world face, the dangers they take looking for hereditary flawlessness. In Josie’s debilitated room, she and Rick embrace an odd custom suggestive of the understudies’ artistic creations in Never Let Me Go. Josie draws personifications of individuals and Rick composes thought rises for them, enlightening profound facts regarding the distracted, fatigued grown-ups, the desolate, debilitated youngsters. These portrayals before long interpretation of a profound emblematic import, a portrayal of the force of workmanship to communicate the inferred.

Klara’s voice has the very overwhelming effortlessness that we found in Kathy H in Never Let Me Go, a similar combination of insight and naivety. Ishiguro has unmistakably contemplated those components of an incipient mechanical cognizance that would be pretty much evolved, regarding what confidence would resemble to an android psyche, or love, or unwaveringness. It’s the contemporary resonances that hit hardest in the novel, however. Ishiguro had evidently nearly completed the original when the pandemic hit, yet on pretty much every page there’s a section that feels frightfully insightful of our secured, worried, mysophobic occasions. To be sure, the account of Klara and the Sun is empowered by the grating between two unique sorts of adoration: one that is egotistical, overprotective and restless, and one that is liberal, open and generous. It seems like a directive for us all as we approach our terribly delineated days.

Never Let Me Go and The Buried Giant were both, for every one of their disparities in setting and topic, dim purposeful anecdotes that spoke about the risk of unchecked mechanical advances, the deficiency of blamelessness, the poise of basic lives. It’s bizarre, yet Klara and the Sun makes the connections between those past two books more evident, recommending that the three books could nearly be perused as a set of three. What’s certain is that Ishiguro has composed another magnum opus, a work that causes us to feel once more the magnificence and delicacy of our humankind.